As March comes to a close, so does National Women’s History Month and that means (although it’s never NOT a good time) it’s a good time to take a look at women and money. Specifically, where women are falling behind in regards to wages versus men.

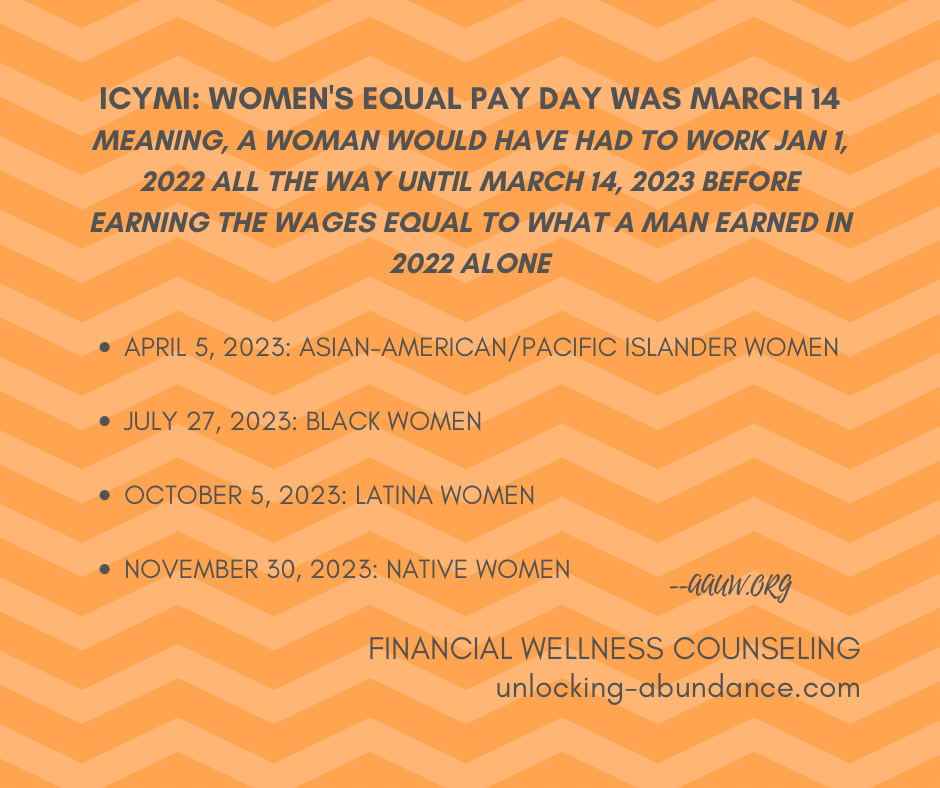

ICYMI: Equal Pay Day fell on March 14th this year. Read below for the history of the recognition of the day and how it is calculated, and most importantly, why women are falling behind and what can be done now to address the pay disparities.

History of Equal Pay Day:

Equal Pay Day originated in 1996 by the National Committee on Pay Equity as a PSA (public service announcement) in order to shed light on the gap between women’s and men’s annual wages. It was becoming clear that women (although over half of the population) earned less, on average than men, in the same year. Since then, additional pay gaps have been discovered between women themselves; the wage gap between women and men widens further when checking the numbers of women of color and their earnings against white men.

How Equal Pay Day is Calculated:

Just how much longer must women work to be caught up to men over the course of a year? That’s when math comes in. In 2023, among full-time workers, US census data shows that women (as a whole) earn 84 cents for every dollar paid to men. That means, they have to work an additional 16%, over the time of one year, to be caught up to men. Therefore, if both groups began working on January 1 of 2022, women would need to continue working until March 14 2023 in order to match what men had made at the end of 2022.

The gap between the wages women earn versus men is further broken down for these groups of women:

–Asian American/Pacific Islander Women: 92 cents for every dollar.

–Black Women: 67 cents for every dollar.

–Latina Women: 57 cents for every dollar.

–Native Women: 57 cents for every dollar.

Why are Women Falling Behind in Pay:

The entire economic system of work-for-pay was set up to support white men at work while women stayed home and provided caregiving, and change takes time. Remember, women could not even legally have a credit card in their names without a man as co-signer as recently as 1974. While straight up sexism does play a role in holding women back at organizations (for example, when women are paid less than men for the same work at the same company; see The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009) there are some other subtleties in the workplace that appear minor on the surface, but add up to significant hurdles against women advancing at the same pace of men.

Two of these hurdles are “non-promotable work” falling on the shoulders of women, and the fact that women are usually expected to act as primary caregivers when it comes to work/life balance in the home. Non-promotable, or unrewarded work, often falls on the time of working-women: taking notes at the meeting, planning the social functions in the company, acting as workplace therapists in order to resolve conflict, etc. Women are expected to and end up spending more of their time in areas that aren’t promoting them as fast as men.

The other way is that women in general are expected to be the primary caregiver in the family. This shows up as women typically being the solo adult in the home to step away from work when kids can’t attend school (hello Covid and schooling at home!) as well as giving care to an elderly family member. The pandemic alone showed that a greater number of women left the workforce compared to men. “About 44 percent of women said they were the only one in their household providing care when schools and day-cares shut down, compared to just 14 percent of men.” Tracking the Progress of Women in Academia 7/8/2020

How We Can All Get Closer to Pay Equity:

First of all, both organizations and men need to voice that they want pay equity. If only the women are speaking up, the needle only moves so far. If men demand to see change within an organization, that’s a win-win-win for the company, the workers and women.

While women themselves can work on their negotiation skills and up their confidence factors by building financially savvy communities amongst other women where pay-transparency and support is available (research shows that women won’t even apply for a position unless they feel close to 100% qualified while men will apply if they feel 60% qualified) the burden actually falls on the organizations and employers themselves to recognize the disparities in their own companies. This could look like recognizing the needs of women and all employees as the primary caregivers they are, listening and evaluating flexibility on everything from work-hours required to hybrid/remote working opportunities. Prioritizing DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) efforts which are becoming slowly more visible at larger corporations will also be impactful by setting the stage for expectations at companies of all sizes. Let’s keep moving forward!