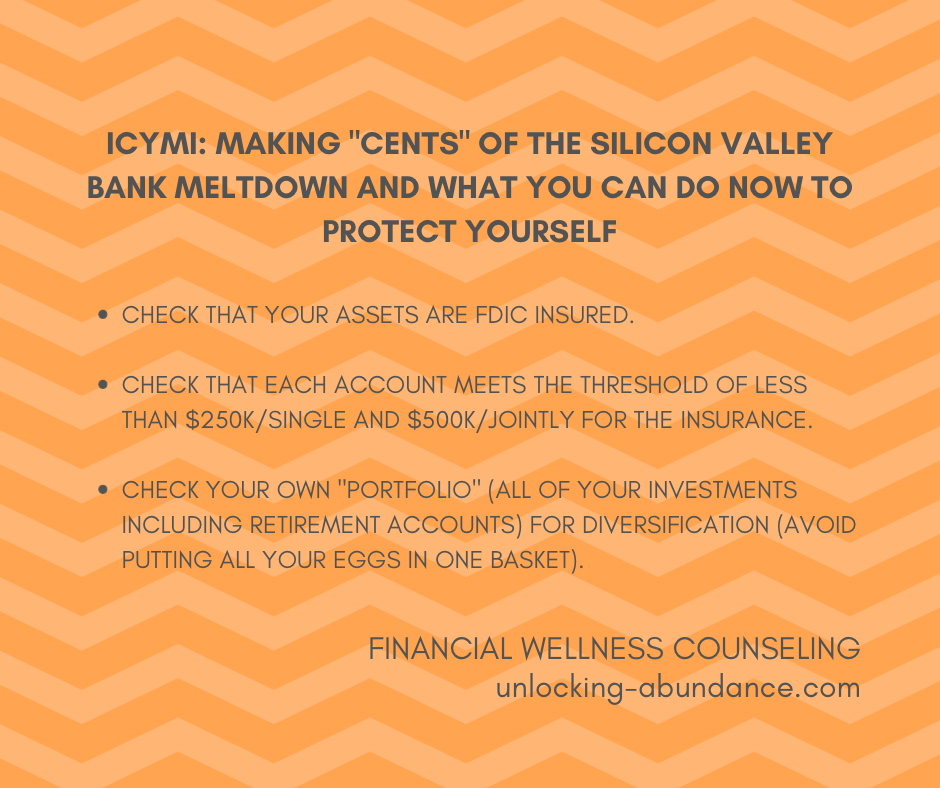

Whew! What a week of some uncommon flux in the banking sector—a spot we’ve all collectively come to trust as “the place” to house our money! Read below for a brief history on how banks actually operate, and what went down at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). Most importantly, find out the lesson we can all learn here, and what we should and shouldn’t be doing regarding banking moving forward!

Briefly, How Banks Operate:

We’ve trusted banks with our money for so long, but when was the last time we took a moment to question what exactly are they doing with our money?! Well, banks are businesses like all the others, and need to make a profit. They take our deposits and then invest them into traditionally “low risk investments” so they can essentially use our money in order to make more money. They do this in exchange for managing our money for us, and lessoning our risk of mismanaging it if we were to keep at all at home in cash.

If they are Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured, they also provide us with the peace of mind of knowing that each account (more on the importance of this below) we have is insured to be made whole, up to $250k/single and $500k/jointly, should anything go down at the bank.

What Went Wrong at SVB:

This is not the first time a bank has failed (WA Mutual 2008 was the biggest and latest) but this situation appears to be a particularly perfect s-storm of events. The customers of this bank were overwhelmingly wealthy corporations (tech start-ups, venture capitalists like Etsy, Roku, etc.), so they were already pushing way past the FDIC limits. It’s reported that 90% of the accounts at this bank were already over the limits which left them way out of balance in the ability to make their customers whole if needed. Throw into the mix the rise of interest rates lately (in trying to get things back to normal after a once-in-a-century pandemic) and those “low risk investments” the bank was investing their customer’s funds in were not yielding the bank the returns they could usually count on. Also, add in the effect rising interest rates had on the tech industry particularly (again, the rise of interest rates meant lots of layoff’s lately) most businesses that banked at that bank had started tightening their belts and pulling more money out. Not a good sign.

So, the bank, recognizing these factors and seeing the writing on the wall, took a drastic measure and sold off a huge chunk of it’s investments in a 48hr period. These sell-off’s were at a loss and didn’t do much good for the bank in the short term. As expected, the customers took notice and came running for their money (literally called “a bank run”). If you’ve seen It’s a Wonderful Life, you know this image; everyone storms the bank and the bank doesn’t have enough cash on hand to fulfill the requests.

In a weird twist, and not the focus of this article, the FDIC, Treasury, etc. has promised to make all account holders whole (thru bank reserves designed for times just like these and not at the expense of the taxpayers in other instances) because they deemed this bank to be a threat to the entire banking system, regardless of the insured amount threshold.

A Few Things for the Average Person to Consider Now:

This situation provides us with the opportunity to check on our own accounts and consider what’s going on at both a micro (right up close) and macro (birds-eye view) level.

First, check your money and it’s eligibility for FDIC insurance.

Are your assets at an institution that is FDIC insured and do you fall below the FDIC threshold? Again, this is per account so consider opening additional accounts if you’re above the limits. We talked about the different accounts available for stashing your savings.

Next, check your diversification across all investments (retirement accounts, brokerage, etc.) and consider spreading things around if they seem unbalanced. SVB is a classic example of investing heavily in one area and one area only—technology. When that area takes a hit, consequences are felt.

What the Average Person Shouldn’t Do Now:

This particular meltdown at SVB bank does not reflect the average banking institution (as was noted, most of the accounts there surpassed the FDIC limits) and therefore it was reasonable that customers would be concerned about their money. If the average banker was to panic and rush their bank now (particularly if they have less than the required amount for FDIC to kick in) the panic would not be reasonable or rational. It would cause more harm than good.

Check your accounts, check your insurance, check your diversification, and keep moving forward!